Introduction

With the rise of streaming services, it seems that there’s an overabundance of new series debuting to keep up with. Differing from the way we’ve consumed media in past decades, via cable TV or movie rental stores, now with the vast expanses of multiple streaming services, the landscape has become oversaturated with options. But there’s one series that multiple cable networks rejected, where Netflix saw potential. Netflix’s Stranger Things was created and written by the Duffer brothers and debuted on the platform in 2016 before going on to become the most streamed show in 2022, amassing a total of 52 billion minutes viewed throughout the year, and becoming one of the most globally recognized television series of the past decade. Through media coverage, there has been so much focus on how popular the hit show has become and the numbers it’s raking in, but what I aim to focus on is what it did right to gain such a large, dedicated viewership and become a cultural phenomenon shining through the vast sea of other media to choose from.

Stranger Things is set in the 1980s, following teenage friend group Mike, Will, Lucas, and Dustin, who reside within the fictional town of Hawkins, Indiana. When Will goes missing in an alternate dimension swarmed with monsters, it kick-starts a chain of unusual events as the other three stumble across Eleven, a girl with telekinetic powers that has escaped a government facility, and unexplained events begin to consume the gang’s once peaceful lives. This seems like a fairly straightforward premise that manages to embody beloved classics within the genre, adjacent to that of Steven Spielberg or Stephen King, but Stranger Things sets itself apart from the rest by tastefully executing narratives surrounding sexuality, primarily through the uniquely queer struggle of being alienated or seen as “different” in a world where heterosexuality is viewed as the default.

Narrative

Stranger Things is often discussed surrounding its use of science fiction and horror in a unique way, but a lesser credited genre that it handles is its romantic subplots. A particularly interesting storyline is one that takes place within season three and surrounds the budding relationship between Robin Buckley and Steve Harrington. With the introduction of Robin as a new character being back-to-back with Steve’s break-up with his longtime girlfriend Nancy Wheeler in the previous season’s ending, the Duffer brothers create an assumption for the progression of their relationship the second we meet this new character—she’s here to be Steve’s new love interest.

This is further supported throughout the season. The two can be seen working side-by-side at the mall’s ice cream joint as they engage in playful banter, primarily with Robin teasing Steve for how he’s lost his cool factor and easy ability to pick up girls, even going as far as keeping a scoreboard of all the times he gets rejected. In the earlier half of the season, she even makes an offhand comment about how she’d always stare at Steve in class. The show presents us with these two characters who seem like polar opposites—the nerdy outcast and the popular one—and while the two are initially passive towards each other, they’re repeatedly put into physically up-close scenarios. Whether it be behind the counter of a cramped food court establishment, trapped in a secret elevator that goes underneath the mall itself, or even tied together with rope and beaten up. The use of closed spaces and a lack of personal space sends a suggestion to the viewer that these two characters will become emotionally close too. This notion is supported by a Reddit user, commenting “The teasing, enemies-to-lovers, ‘opposite attracts’ type dynamic is strongly at play with Steve and Robin. They have an outside source (Dustin) comment on their chemistry and Steve trying to deny it. We’ve got Steve and Robin holding hands in a tense moment, and strong feelings coming out when one of them is being threatened. They’ve even got matching outfits to delineate them as a pair.”

Textual Breakdown

All this build-up comes to a head when after being beaten up and drugged with truth serum, the two hide in a movie theater bathroom before having a heart to heart with one another. The scene frames the two in side-by-side stalls, with only a thin wall standing between them acting as a symbol of divide between the two. Robin asks Steve if he’s ever been in love, to which he responds that he’s found somebody better suited for him than Nancy, which supports my evidence that Robin being introduced right after their break-up was no mere coincidence. Steve goes on to admit that the girl he likes is one that he never acknowledged in school, and we can see that Robin looks tense and guilty as her shoulders slouch while she listens to him pour his heart out to her, confessing that he hasn’t laughed as hard as he has with her. For the most part during this, we’re able to see a close up of Robins reaction to his speech, and it tells the viewer everything they need to know – she’s not happy, rather she looks heart broken as she rests her head against her knees. After a long moment of silence, Steve moves to be in the same stall as her, signifying that the walls between them are about to come down as she confesses to him that she wasn’t staring at him in class because she had a crush on him, but rather because she was jealous that the girls gave him the attention she wanted from them. In return, Steve is more surprised than anything. He doesn’t get mad, he doesn’t try to change her, instead, he jokes around to make her feel less uncomfortable. Even though he’s the one that’s heartbroken, he proves his emotional maturity in this scene by acknowledging how tough coming out must have been for her.

The same previous Reddit user adds to their statement, “None of these things inherently indicate anything about Robin or her sexuality, but we make assumptions based on what we expect these scenarios to mean. We don’t even expect that there’s anything to expect about Robin’s sexuality! We assume, as we’re conditioned to, that this is all in service of romance.” And that’s precisely how the Duffer brothers played into engagement by diverting those very expectations and tropes that audiences have become accustomed to within the genre of teenage romance.

This season long dupe is so important, not only within the context of the show but also to the contextual future of other media, because it manipulates viewer’s expectations in a way that reflect real world issues. Media has widely supported the notion of heteronormativity for decades, and by leaning into all of these common tropes that audiences have come to understand and associate with romance in mainstream media, the Duffer brothers blow away everything that the audience expected by going against the status quo.

Ideology

Continuing with the themes of sexuality displayed throughout the show, we go into season four where the focus is shifted to Will coming to terms with his crush on Mike, who has an established relationship with Eleven at this point. In Western media, heteronormativity runs rampant and the very real world issue of LGBT+ people and relationships being seen as “other” is an all too common narrative. Stranger Things challenges this real world belief by drawing parallels on the striking similarities between straight and queer couples, while also making sure not to undermine the unique experiences that queer people go through navigating these relationships.

It starts in the opening of season four, where Will can be seen working on a painting that Eleven speculates is for a girl he likes, only for the truth to be revealed later in the season when he gifts the painting to Mike. Here we’re given hints of a potential heterosexual relationship that never comes to fruition, with Eleven just assuming that since Will is a boy he will by default have a crush on a girl. I want to note how the show immediately addresses the issue of heteronormativity through this scene as throughout the show, Eleven, being unfamiliar with humans, has to learn all her perceptions about the world through her surroundings and what she sees in media, mirroring the way real audience’s perceptions have been molded by heteronormative formulas and tropes.

After presenting Mike with the completed painting, Will goes on a monologue about Eleven, saying, “These past few months she’s been so lost without you. She’s just so different from other people. And when you’re different, sometimes you feel like a mistake. But you make her feel like she’s not a mistake at all, like she’s better for being different. And that gives her the courage to fight on. If she seemed mean to you or if it was like she was pushing you away, it’s just because she’s scared of losing you like you’re scared of losing her. And if she has to lose you, I think she’d rather just get it over with quick, like ripping off a Band-Aid. She needs you Mike, and she always will.”

On paper, Will’s speech seems straight forward. But the visuals presented alongside the dialogue give the audience a different angle of the story. As Will begins talking about how lost Eleven has been, the camera flashes to his older brother Johnathan, who is driving, before he looks in the rear view window and we get to see the two boys from his point of view. Why is Johnathan’s reaction important if this is supposed to be about the relationship between Eleven and Mike? Because it’s really not. Samantha Coley writing for the Collider supports this when she writes, “In the episode, Will unveils his painting from Volume 1 and explains the complexities of El and Mike’s feelings for each other. To Mike, he’s talking about Eleven, but for Will, Jonathan, and the audience, we can see that he’s also talking about himself.” This is a powerful scene commentating on the ideology surrounding heteronormativity both on screen and off. It proves how only looking at a situation from one angle, in this case that being only the script without the visuals, leaves a lot of subtext out of the conversation.

Mike is looking at Will as he speaks, but Will is avoiding his gaze by looking out the window as he’s delivering the line, “And when you’re different, sometimes you feel like a mistake.” The way his voice becomes hoarse and tears well in his eyes tells the viewer that he’s resonating with the words he’s saying, rather than simply saying them on behalf of Eleven. And yet, at the same time, I believe he’s deeply relating to Eleven and how they’re both perceived as straying from the status quo.

Eleven and Will’s feelings and the situations that they’re put in parallel each other because they both have romantic feelings towards Mike. This has been made reference to subtly throughout the series, with bullies calling Will a gay slur, Will getting particularly jealous of Mike giving Eleven attention in multiple instances, Mike accusing Will of “not being into girls”, but maybe the most damning allusion would be that after his speech is done, Will turns to the window and covers his mouth to suppress his crying. All of these instances go to highlight the unique complications that come with being queer.

Will’s speech would make perfect sense with the story line even if you swapped Eleven’s name with Will’s and had him speak in the first person. By doing this, Stranger Things addresses the hegemonic ideology that heteronormativity is the natural default and challenges it by re-framing a heterosexual romance with a queer narrative, thus managing to blur the lines of what people think makes each sexuality different from one another.

Industry

While Stranger Things has become a household name, by no means have the marketing department slacked off on flashy promotional stunts. If anything, it gave them more incentive to go above and beyond. Taking one look at even a promotional image can give you a glimpse into the upside down world of Stranger Things, but the marketing campaigns chose to go far beyond a still image as they aimed to immerse viewers into the world of Hawkins, Indiana in a way that not many other franchises have done. While similar franchises have chosen to engage in immersive experiences by creating theme parks surrounding their franchise’s world building, Stranger Things does it differently by using experiential marketing to build hype around upcoming seasons.

By posting a string of coordinates to their official Twitter account, they put viewers in the pilot seat to solving the mystery – much like the main characters have to do to solve their own strange happenings. Fans soon found that the coordinates could be traced back to 15 different landmarks, like New York City’s Empire State Building or India’s Gateway, scattered across 14 countries where giant rifts were projected, connecting The Upside to our world (Vejvoda “Stranger Things […]”). Not only was this an interactive experience for those on Twitter, but it acknowledged the international fans, something other franchises may fall short of recognizing the importance of.

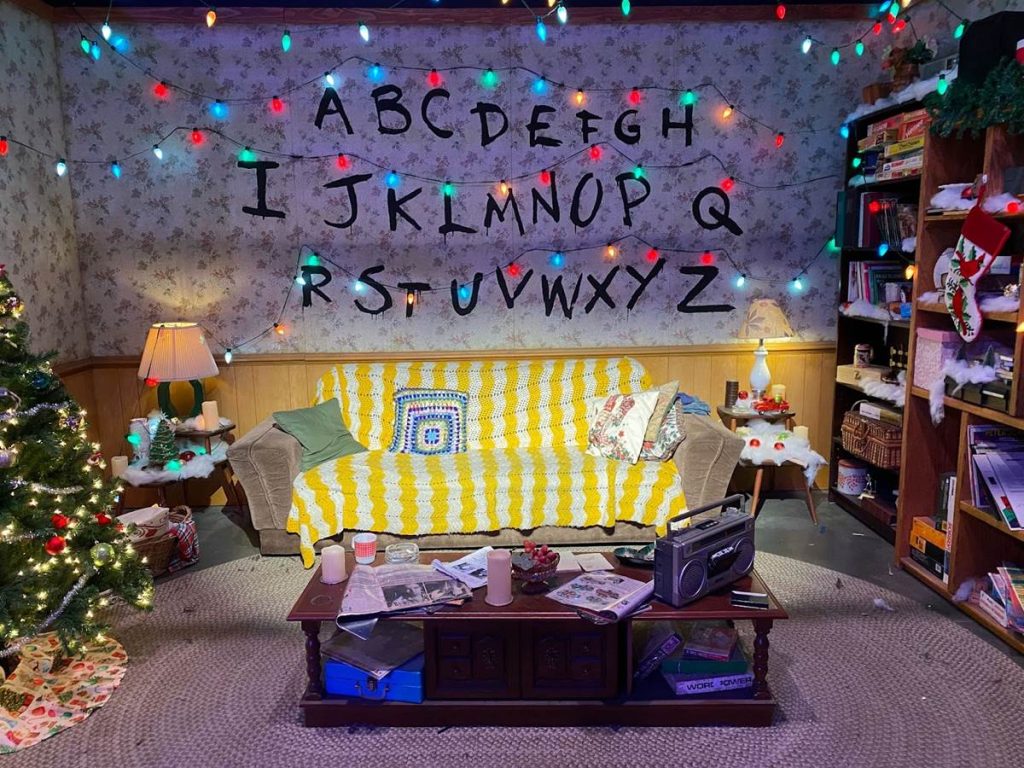

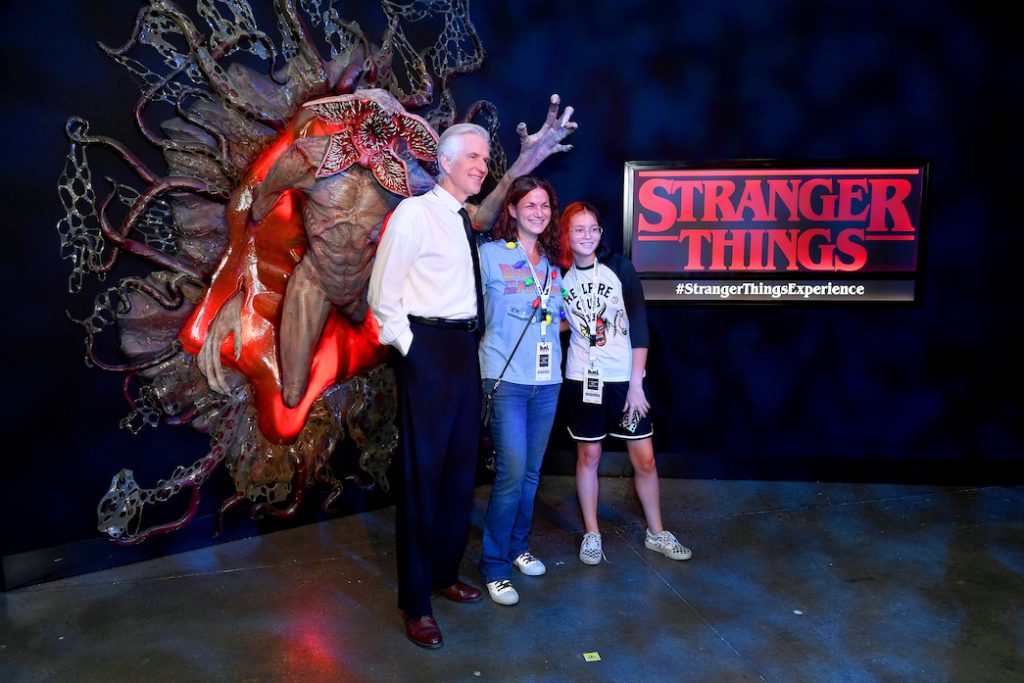

With a show all about fantastical alternate dimensions being homed right underneath our feet, this gives a lot of room for creativity in marketing tactics. Which is exactly what the team did when they set up pop-up locations of “Stranger Things: The Experience” throughout the USA, Canada, and the UK. These locations included recreations of iconic sets from the show like the Upside Down, a chance to get up close to various monsters, and a rotation of actors that stayed in character as if it was all really taking place in Hawkins. Erica writing for Web Content Development writes about the whole event, saying, “Because the Experience hit cities before the show aired in late May, the famous show’s views skyrocketed. Experiential marketing satisfies where traditional marketing cannot. It allows people to become a part of the brand, not just passive consumers. If it weren’t for the ingenuity of experiential marketing, Stranger Things might not have reached its noteworthy billion views.” The use of experiential marketing ended up being a phenomenal advertising decision because not only did it connect the fans relationship with the show in a memorable and personal way, but it also allowed them to become fully immersed into exploring its universe(s).

To further blur the line between what we see on screen and real life, actor Matthew Modine, who plays the scientist Dr. Brenner on the show, even made a surprise appearance at the New York location. In response to the actor’s appearance, Charles Taylor for Forbes wrote, “By providing a special experience for those physically present as well as a feel-good story for those exposed to media coverage of the event, deep loyalty can be fostered.” He makes a good point by mentioning how even fans who couldn’t attend the event can feel vicariously joyed watching the efforts that the show goes to to give back to its fan base, thus appealing to an even wider variety of the audience.

For a show as widespread as Stranger Things, they could have probably whipped up some promotional posters, relied on Netflix’s advertising, and still bag millions of viewers. But rather than advertising in a standard way that would be cheaper but may still be just as effective, they went that extra mile to bridge the gap between brand and consumer by directly connecting them to the show and giving back to the audience by creating lasting memories.

Conclusion

Stranger Things’ deserves more credit than its given as it’s not just a series that gained its ratings from pure luck. Beyond its star studded cast, neon lights, and catchy 80’s synth, a lot of creative liberties and attention to detail were put into it to make it a show that is as much about the humane struggles of feeling alienated than it is a show about actual aliens. While inspiration drawn from the likes of Stephen King, Steven Spielberg, or Dungeons and Dragons can be seen strewn throughout, Stranger Things makes a name uniquely for itself through narratives that resonate with viewers through the comparison that even humans can feel like aliens. By delving into the such expanse detail about the worlds the show has created, it’s able to engage viewers both on screen and within its experiential marketing while giving back an experience for the dedicated audience that made the show a massive success. By combining visuals and dialogue that contradict one another, it challenges audiences to rethink expectations that we’ve become accustomed to surrounding how romantic relationships are handled in mainstream media. All of these points culminate to say that Stranger Things is an exceptional carefully and considerately crafted piece of modern media that manages to diverge your expectations into a narrative that proves more complex and realistic than you’d initially think on the surface.

Works Cited

Coley, Samantha. “Will’s Speech to Mike in Stranger Things Season 4 Episode 8 Explained.” Collider, 4 July 2022, collider.com/stranger-things-season-4-will-byers-speech-car-scene-sexuality- duffer-brothers-comments/.

Erica. “Experiential Marketing: How It Helped Broke Records for Stranger Things.”

Webcontentdevelopment.com, 2 Sept. 2022, www.webcontentdevelopment.com/how-stranger-

thingss-experiential-marketing-helped-it-break-netflix-records/.

Taylor, Charles. “How Netflix Is Resonating with “Stranger Things” Fans through Experiential

Marketing.” Forbes, 31 Aug. 2022, www.forbes.com/sites/charlesrtaylor/2022/08/31/how-

netflix-is-resonanating-with-stranger-things-fans-through-experiential-marketing/.

Vejvoda, Jim. “Stranger Things Season 4 Fan Event Will See Rifts to the Upside down Open Worldwide.” IGN, 25 May 2022, www.ign.com/articles/stranger-things-season4-part1-global- fan-event-light-shows.