Subtopic #2

Field hospitals were almost non-existent prior to the Korean and Vietnam war. The first forms of medical treatment during war consisted of medical personnel on the field 1. The medical staff would try and treat the wounded in order to keep them alive or until an evacuation to local hospitals became available. This system led to many deaths due to the length of time it took to get the wounded from the battlefield to a safe place for proper medical treatment1. This lead the government to work towards changing battlefield medical treatment plans. During the span of World War I the government tried and tested different forms of field hospitals. The potential of a working hospital would not only save more lives but also get wounded soldiers back into battle sooner. The first step was to locate the hospitals closer to the front line, as well as station Drs in the field; this was in hopes to cut evacuation and response times down from prior wars1. However, these efforts didn’t work because the time it took to get to local hospitals equaled the same amount of evacuation time to these newly built hospitals. The second type of field hospital the government tried was a bit more successful. It involved attaching ‘hospitals’ to division stations, moving both surgeons and platoons closer to the front line. While this worked in terms of locations, the ‘hospitals’ did not have the proper equipment to treat the critically wounded and ended up needing to evacuate them1. The third form prompted immediate care for the wounded; by assigning one medical personnel to each evacuee before medical evacuation1. This was also the birth triage, they started helping those with lesser injuries on site and evacuate those only critically wounded. By having a designated person per each evacuee it was expected to have a lack of lag in between the evacuation and hospital evaluation process. During World War II, the government had placed hospital units alongside military units once more. These units consisted of three to four smaller medical units that had a 400 bed capacity. Soon the problem of lack of mobility became a concern. The units weren’t designed for travel, as the front line moved farther and farther away from the problem regarding evacuation popped up again1. This lead the government back to the drawing board, needing a design that could travel with the troops as well as have enough space to treat everyone. That was until the Korean and Vietnam War. In which field hospitals improved drastically; medical techniques, location, and evacuation methods are just some of the things that were updated during these times of war.

“Tent setup” Apel,John, and wiest, Andrew A.” A Window of Opportunity: A history of the Mobile Army Surgical Hospital in the First Half of the Korean War (1998):Proquest Dissertations and Thesis.http://www.odu.edu/librry.10/3/18

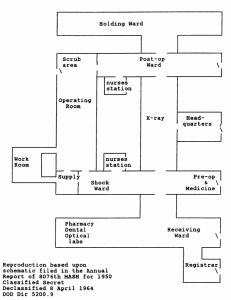

The government designed a unit formed from the best aspects of the field hospitals prior to this time. Thus the creation of the Mobile Army Surgical Hospital, M.A.S.H for short was created7. M.A.S.H. was created in 1994, these units were designed to follow the troops to the front line by being quick and easy to transport. The typical M.A.S.H unit consisted of a series of nine tents designed to be constructed in a “U” and “I” shape and could be packed up and ready to transport in an hour7. These layouts were created to help fluctuate patient flow in order to ensure faster time between soldiers being wounded and getting back on the front line. In the “U” shape the first side was designated for pre-op patients, the bottom of the “U” was the designated surgical area, and the final end of the “U” was for post-op patients. The “I” shape holds the rest of the hospital; the top part of is the holding ward, the middle part of the “I” is for X-ray, and the bottom part is for the receiving area the pharmacy the dental ward and the optical labs7. The original plan consisted of 126 staff members7; 14 Drs., 12 nurses, 2 medical service corps officers, 1 warrant officer, and 97 enlisted officers. The 14 Drs. and 12 nurses were then divided by specialty or different assignments. The 14 Drs. consisted of 3 general surgeons, 2 anesthesiologists, 1 radiologist, 3 assistant surgeons, 2 internist, and 3 general duty medical officers. The nursing staff had 1 chief nurse, 6 general, and 5 OR nurses. The units contained 200 beds, a registrar, a central supply room, headquarters, a lab, and a pharmacy; but despite this ideal setup, the field hospitals faced a lot of hardships7.

The conditions of the M.A.S.H units varied based on the location of the unit. During the Vietnam War, the units battled weather conditions, terrain, and the constant threat of enemy fire. These units were not introduced to the public until after the war in 1972. Due to a popular T.V. show “M*A*S*H” the world learned about Mobile Army Surgical Hospitals7. The show followed medical personnel stationed at 4077th Mobile Army Surgical Hospital. Not only did the audience watch the surgeons fight to save soldiers from horrifying injuries, but fight the rough conditions as well.

Despite the ‘roughness’ of the units that were depicted in the show, the conditions of the actual units were much worse. The terrain these M.A.S.H units faced included jagged mountains, low hills, and marshy fields. The summers were hot, reaching up to 110 degrees and were humid7. It was reported that the heat got so bad that the Drs. needed to change gloves multiple times during surgery due to gloves filling with sweat. During the winter temperatures reached 30 below; with thin tent flaps and no heating or air conditioning units, there was little to protect those inside from the harsh weather7. Another thing that the units dealt with was the prospect of enemy fire. Due to M.A.S.H units being as close to the front line as possible, they often risked being caught in the crossfire. One account of this is seen with the M.A.S.H 8076th unit; the battle front moved closer and closer to them at a fast rate, while trying to pack up the unit, Lieutenant Colonel Van Buskirk radioed others to find out how much time they had. He did this frequently hoping to just miss the battle until he radioed once more asking “where is the battle now?” to which the person responded “ your standing on it”7. Luckily, the unit was able to escape the battle with minimal damages to the structure and minimal casualties. Along with all of these issues, the staff were shipped off with little to no field training. Due to the short five year window between the creation of the M.A.S.H unit and the start of U.S involvement in the Korean War, there was not enough time to properly train all medical personnel for what was to come. In fact, many of the doctors that weren’t designated for general surgery practiced it in these units due to the unexpected influx of surgical cases; hence the phrase “every doctor became a surgeon”1. Despite the lack of training the staff was expected to work long hours, without any breaks, in order to treat as many patients as possible. It was estimated that the 200 beds ended up seeing roughly 400 patients a day1. One case that was reported was of a doctor needing to be cut out of his shoes due to standing for so long. The staff also had to deal with the lack of amenities; the units often lacked typical properties of hospitals. Things like no bright lights in the OR, lack of proper sterilization, and lack of stereotypical washing stations; Drs. often relied on a gallon jug with holes on the bottom to wash in between surgeries7. This environment took a toll on everyone, the Drs., the soldiers, and the nurses. In fact, there have been many articles covering how the Korean War affected nurses specifically. Many nurses who enlisted in the army had worked in treating ‘basic everyday’ injuries. The wounds seen in this was different than anything they saw before; multiple bullet wounds, land mine related injuries and abundance of frostbite cases where just some of the injuries they treated. In most cases, the nurses reported the need to detach from the situation in order to keep emotion out of the treatment19. They had to help so many patients, many of which went back to the battlefield the same day. If they got attached to every patient they worked with, the emotional trauma of losing them could be too overwhelming. Despite the intensity that the M.A.S.H units dealt with, they brought a lot to the medical field. In previous wars, many lives were lost due to the slow evacuation times. During the Korean War, the army began to use helicopters in combat and for medical evacuation. This contributed to the drop in the death rate from 4% in World War II to 2.5% in the Korean War1. During this time triage evolved immensely from the original separation of superficial wounds and critical injuries. Now wound categories were based on an accumulation of all injuries that were assessed by the doctors or nurses upon entering the units; this allowed an easier system for creating an order of surgeries1. This also created an easier flow to the hospital, by organizing the patients the staff didn’t have to rush around and risk going out of the surgical need order. During this war, another thing that improved was patient care. In the OR, they transitioned from the use of Chloroform and Ether due to the negative inotropic effects to nitrous oxide7. Drs also used Thiopental in small amounts due to the risk of respiratory depression that occurred when used to loosely. For rapid intubation, Drs relied on tubocurarine and succinylcholine7. At this time doctors started using penicillin to treat wounds and fight against potential infections. Although it was soon realized that the penicillin was not working on injuries related to bullet wounds and explosions. It was then concluded that the reason why the antibiotic wasn’t working was due to incomplete debridement of the wounds; this lead to the push for a thorough debridement of each wound7. Another surgical improvement that occurred during the Korean War was the improvement of vascular surgery; surgery that is solely focused on the vascular system, arteries, veins, and circulation. This was important because it lowered the number of amputations; before the Korean War many amputations that occurred due to not being able to properly save the veins of the extremities7. With the new improvements, the amputation rate dropped from 36% during World War II to 13 %. Overall the M.A.S.H units helped the death rate decrease immensely and were greatly valued by the government due to their mobility and adjustment to the terrain. They are one of the best field hospitals created by the government and are still used today because of it.

“Inside look at the M.U.S.T unit” King, Booker, and Ismall Jatoi.”The Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH): A medical ASsociation 97.5(2005):648-56: http://www.odu.edu/library,10/2/18

The Vietnam War was different than any other before due to the guerrilla tactics used by the Viet-cong; forcing the U.S to change tactics to updated hospital units. Following the success of the M.A.S.H units, the government opted to keep the basic design and simply updating it to match the needs of the Vietnam War. Thus the creation of the Medical Unit Self-Contained Transportable, M.U.S.T for short1. Unlike the M.A.S.H unit, the M.U.S.T units weren’t originally designed to follow the troops into battle, but to remain in a set location and have patients transported to them. This increase in response times made the death rate spike. Also, the hospitals’ location could be easily located by the enemy. Following the death of Major Gary P. Wratten, the hospital commander; the U.S. Pacific command surgeon ordered that all M.U.S.T units become mobile in 19681. These units consisted of 13 ft long inflatable tents, that were powered by a turbine generator which fed the unit’s exhaust; making the unit’s self sufficient28.

There were 5 major sections, the hospital, debridement ward, ICU, radiology and dental. There was also a pharmacy and kitchen1. These sections were equipped with heating and ac units as well as electrical. Due to all the advances that were made during the Korean War, the problems faced in the Vietnam War were completely unique. An example of this is seen with a disease that appeared during this time; Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome, also known as ARDS1. These casualties with severe hemodynamic compromise required massive blood transfusions and were not seen in earlier conflicts. Soldiers who were compromised often died in transport too. Initially, the surgeons at M.U.S.T used diuretics and fluid restriction as the treatment for ARDS but had no success. At first, the only way to diagnose ARDS was purely off of suspicion, and the best diagnostic tool for this illness, the chest radiograph was not invented yet1. With the use of Agent Orange and other chemical agents, the number of chemical burns was higher than in any previous conflict. However, with the invention of Sulfamylon, a topical medication that is applied to wounds before placing the dressing on and the realization that fluid resuscitation was important in the treatment of burns1. The mortality rate for burn patients reduced by 50% compared to the Korean War. Despite the efficiency of the M.U.S.T unit, something that they lacked was a productive system for blood distribution. Originally all blood that was donated to the war efforts was regulated at the 406th medical lab in Japan. It was then sorted and distributed to Vietnam, which was a lengthy process. This lead the government to create the Armed Services Blood Program1. In which mobile teams were created to procure and distribute blood to hospitals and the medical units in Vietnam. All specific blood was then sent to the 406th and all universal donor O-negative blood was transported directly to Vietnam. With this new process of blood distribution came the discovery that by storing the blood bags in styrofoam containers before refrigerating, it gave the blood a longer shelf life. These findings and inventions of the M.U.S.T units saved thousands of lives during the Vietnam War and continue to do so today.

In conclusion, the M.A.S.H and the M.U.S.T units greatly changed the definition of field hospitals. They created new medical techniques, new evacuation, and transport methods and procedures. They offered alternate locations for hospitals and continued to improve medical practices as needed. They continued to grow and change to meet the needs necessary for the current conflict. The M.A.S.H units are currently utilized today, although they are updated with new technology and equipment for all weather conditions and terrain. The staff techniques and programs that these units established have remained in use today and continue to advance with medicine improvements such as utilizing better sterilization methods. These units changed the face of wartime medicine and care and will continue to be used in the future. This topic is significant today due to the continuation of conflict in the world and the new types of warfare being used.

- King,Booker, and Ismalil Jatoi. “The Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH): A Military and Surgical Legacy.” Journal of The National Medical Association 97.5 (2005): 648-56: http://www.odu.edu/library. 10/2/18 ↩

- King,Booker, and Ismalil Jatoi. “The Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH): A Military and Surgical Legacy.” Journal of The National Medical Association 97.5 (2005): 648-56: http://www.odu.edu/library. 10/2/18 ↩

- King,Booker, and Ismalil Jatoi. “The Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH): A Military and Surgical Legacy.” Journal of The National Medical Association 97.5 (2005): 648-56: http://www.odu.edu/library. 10/2/18 ↩

- King,Booker, and Ismalil Jatoi. “The Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH): A Military and Surgical Legacy.” Journal of The National Medical Association 97.5 (2005): 648-56: http://www.odu.edu/library. 10/2/18 ↩

- King,Booker, and Ismalil Jatoi. “The Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH): A Military and Surgical Legacy.” Journal of The National Medical Association 97.5 (2005): 648-56: http://www.odu.edu/library. 10/2/18 ↩

- King,Booker, and Ismalil Jatoi. “The Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH): A Military and Surgical Legacy.” Journal of The National Medical Association 97.5 (2005): 648-56: http://www.odu.edu/library. 10/2/18 ↩

- Apel, John, and Wiest, Andrew A. “ A Window of Opportunity:A History of the Mobile Army Surgical Hospital in the First Half of the Korean War.” (1998). ProQuest Dissertations and Thesis. http://www.odu.edu/library. 10/3/18 ↩

- Apel, John, and Wiest, Andrew A. “ A Window of Opportunity:A History of the Mobile Army Surgical Hospital in the First Half of the Korean War.” (1998). ProQuest Dissertations and Thesis. http://www.odu.edu/library. 10/3/18 ↩

- Apel, John, and Wiest, Andrew A. “ A Window of Opportunity:A History of the Mobile Army Surgical Hospital in the First Half of the Korean War.” (1998). ProQuest Dissertations and Thesis. http://www.odu.edu/library. 10/3/18 ↩

- Apel, John, and Wiest, Andrew A. “ A Window of Opportunity:A History of the Mobile Army Surgical Hospital in the First Half of the Korean War.” (1998). ProQuest Dissertations and Thesis. http://www.odu.edu/library. 10/3/18 ↩

- Apel, John, and Wiest, Andrew A. “ A Window of Opportunity:A History of the Mobile Army Surgical Hospital in the First Half of the Korean War.” (1998). ProQuest Dissertations and Thesis. http://www.odu.edu/library. 10/3/18 ↩

- Apel, John, and Wiest, Andrew A. “ A Window of Opportunity:A History of the Mobile Army Surgical Hospital in the First Half of the Korean War.” (1998). ProQuest Dissertations and Thesis. http://www.odu.edu/library. 10/3/18 ↩

- Apel, John, and Wiest, Andrew A. “ A Window of Opportunity:A History of the Mobile Army Surgical Hospital in the First Half of the Korean War.” (1998). ProQuest Dissertations and Thesis. http://www.odu.edu/library. 10/3/18 ↩

- Apel, John, and Wiest, Andrew A. “ A Window of Opportunity:A History of the Mobile Army Surgical Hospital in the First Half of the Korean War.” (1998). ProQuest Dissertations and Thesis. http://www.odu.edu/library. 10/3/18 ↩

- Apel, John, and Wiest, Andrew A. “ A Window of Opportunity:A History of the Mobile Army Surgical Hospital in the First Half of the Korean War.” (1998). ProQuest Dissertations and Thesis. http://www.odu.edu/library. 10/3/18 ↩

- King,Booker, and Ismalil Jatoi. “The Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH): A Military and Surgical Legacy.” Journal of The National Medical Association 97.5 (2005): 648-56: http://www.odu.edu/library. 10/2/18 ↩

- King,Booker, and Ismalil Jatoi. “The Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH): A Military and Surgical Legacy.” Journal of The National Medical Association 97.5 (2005): 648-56: http://www.odu.edu/library. 10/2/18 ↩

- Apel, John, and Wiest, Andrew A. “ A Window of Opportunity:A History of the Mobile Army Surgical Hospital in the First Half of the Korean War.” (1998). ProQuest Dissertations and Thesis. http://www.odu.edu/library. 10/3/18 ↩

- Tanner, Janet, and Fousekis, Natalie M. “ Nurses in Fatigues: The Army Nurse Corps and The Vietnam War” (2011): ProQuest Dissertations and Thesis. http://www.odu.edu/library. 11/3/18 ↩

- King,Booker, and Ismalil Jatoi. “The Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH): A Military and Surgical Legacy.” Journal of The National Medical Association 97.5 (2005): 648-56: http://www.odu.edu/library. 10/2/18 ↩

- King,Booker, and Ismalil Jatoi. “The Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH): A Military and Surgical Legacy.” Journal of The National Medical Association 97.5 (2005): 648-56: http://www.odu.edu/library. 10/2/18 ↩

- Apel, John, and Wiest, Andrew A. “ A Window of Opportunity:A History of the Mobile Army Surgical Hospital in the First Half of the Korean War.” (1998). ProQuest Dissertations and Thesis. http://www.odu.edu/library. 10/3/18 ↩

- Apel, John, and Wiest, Andrew A. “ A Window of Opportunity:A History of the Mobile Army Surgical Hospital in the First Half of the Korean War.” (1998). ProQuest Dissertations and Thesis. http://www.odu.edu/library. 10/3/18 ↩

- Apel, John, and Wiest, Andrew A. “ A Window of Opportunity:A History of the Mobile Army Surgical Hospital in the First Half of the Korean War.” (1998). ProQuest Dissertations and Thesis. http://www.odu.edu/library. 10/3/18 ↩

- Apel, John, and Wiest, Andrew A. “ A Window of Opportunity:A History of the Mobile Army Surgical Hospital in the First Half of the Korean War.” (1998). ProQuest Dissertations and Thesis. http://www.odu.edu/library. 10/3/18 ↩

- King,Booker, and Ismalil Jatoi. “The Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH): A Military and Surgical Legacy.” Journal of The National Medical Association 97.5 (2005): 648-56: http://www.odu.edu/library. 10/2/18 ↩

- King,Booker, and Ismalil Jatoi. “The Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH): A Military and Surgical Legacy.” Journal of The National Medical Association 97.5 (2005): 648-56: http://www.odu.edu/library. 10/2/18 ↩

- Freemane, Herb. “Dateline: Vietnam.” Leatherneck (pre-1998) 51.10 (1968). http://www.odu.edu/library. 10/3/18 ↩

- King,Booker, and Ismalil Jatoi. “The Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH): A Military and Surgical Legacy.” Journal of The National Medical Association 97.5 (2005): 648-56: http://www.odu.edu/library. 10/2/18 ↩

- King,Booker, and Ismalil Jatoi. “The Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH): A Military and Surgical Legacy.” Journal of The National Medical Association 97.5 (2005): 648-56: http://www.odu.edu/library. 10/2/18 ↩

- King,Booker, and Ismalil Jatoi. “The Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH): A Military and Surgical Legacy.” Journal of The National Medical Association 97.5 (2005): 648-56: http://www.odu.edu/library. 10/2/18 ↩

- King,Booker, and Ismalil Jatoi. “The Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH): A Military and Surgical Legacy.” Journal of The National Medical Association 97.5 (2005): 648-56: http://www.odu.edu/library. 10/2/18 ↩

- King,Booker, and Ismalil Jatoi. “The Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH): A Military and Surgical Legacy.” Journal of The National Medical Association 97.5 (2005): 648-56: http://www.odu.edu/library. 10/2/18 ↩

Recent Comments