Introduction

Millions of cyber-attacks took place across the world in 2022, from the massive state sponsored cyber-attacks from Russia upon Ukraine and her international allies to more domestic attacks like the ransomware attacks that swept across our nation last year. A variety of cyber-attacks were launched against education sectors, government entities, finance firms, and of course healthcare. According to InsiderIntelligence.com, healthcare organizations the world over faced on average over 1,400 cyberattacks per week in 2022, almost double what they faced the year before, as well as some of the largest breaches ever recorded (Phillips, 2023). MediBank, the victim of one of the largest international healthcare data breaches, is still facing fallout to this very day.

/cloudfront-us-east-2.images.arcpublishing.com/reuters/NUVRL477XZISLF4PCGEC6L2S5Q.jpg)

The MediBank Data Breach

MediBank is a name you’ll rarely hear in America, outside of new reports of cyber-attack related reports. Established by the Australian Government in 1976 as a “not-for-profit private health insurer”, they have since grown to be one of the biggest private insurance providers in Australia, covering over 3 million people across the nation (MediBank, 2022). Being one of Australia’s biggest healthcare insurers obviously means they have records and access to data belonging to millions of Australians, a tempting target for any would-be hackers. A target which was eventually acted upon by brazen hackers seeking to steal this information and use it for their own ends.

While the attack is still somewhat recent, information is still coming out about it, but a consensus has generally been reached regarding how the breach happened. To start with, the credentials of a third-party IT-related service provider with high-level access was stolen and subsequently put up for auction on a Russian-speaking dark web forum (Taylor, 2022). From here, the intruders were able to gain access to the Medibank databases and after confirming the credentials were valid, they formulated a plan of attack: after establishing two backdoors into the database to ensure consistent, undetected connection, a script was written to extract customer data automatically from the MediBank database, without attracting much suspicion or notice from the healthcare insurer’s cybersecurity apparatus (Kost, 2023).

It’s unknown how long it took them, but the data (believed to be over 200 GB) was compressed into a .ZIP file and extracted via the backdoors on October 13, 2022. At this point, the breach was detected as “unusual activity”, and the backdoors were closed. With this, MediBank announced to the public that a cyber attack had taken place, but there was currently “no evidence that customer data has been accessed” (Powell, 2023). Despite this public reassurance, on October 19, MediBank was contacted and informed that they had indeed been breached, and the hackers were willing to negotiate in return for the stolen data. They threatened MediBank with the public release of this information and threatened to release data of around 1000 of the most prominent public figures in the stolen data if they could not come to a quick agreement (Powell, 2023).

A day after Medibank was contacted, they confirmed that information had indeed been stolen, and considered their next options carefully. Despite clear evidence of a breach, and the threat of information release, they publicly refused to negotiate, citing the threat to customers via extortion if they agreed to give in to their demands. This decision was made after consulting with well-known cybersecurity professionals and confirming that the deal from the hacker’s perspective was tentative at best, with most of the leverage being in their favor. Despite this brave show of public defiance, the true extent of the breach wouldn’t be known for 2 weeks until November 7th, 2022 (Powell, 2023).

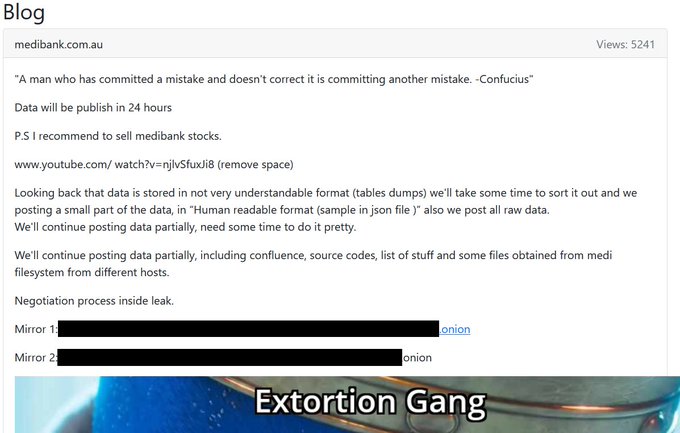

On November 7th, it was finally discovered, and relayed to the public that the hackers had made off with over 9.7 million medical and personal records of MediBank customers, both former and current (Powell, 2023). This includes but is not limited to names, email addresses, birthdays, passwords, past and current medi-care claims, as well as passport and visa information as well. On November 8th, the day after they discovered the true extent of the damage, they received another contact from the perpetrators. It tauntingly included a line from Confucius, as well as a threat that refusing to negotiate would prompt the hackers to release the stolen information on the dark web within 24 hours. They also suggested selling MediBank public shares to help pay for it but still MediBank refused to pay the ransom, further citing their previous belief that it would only encourage them to extort customers directly, and inherent distrust in cyber criminals (Powell, 2023)

Note: The threat included a meme, I’m not joking. The image cut it off mostly.

On November 9th, the hackers followed through on their prior threats, releasing information in the form of a “good list”, and a “naughty list”, the latter comprising notable customers who had received treatment for drug or alcohol issues, as well as mental illnesses. The records were release on a popular ransomware leak site with ties to a cyber-criminal organization linked to REvil, a formerly prevalent ransomware gang comprising almost entirely Russian nationals, and Russian speakers. With this link discovered, investigators noticed a pattern emerge: despite the lack of encryption to the database, the attack followed a distinct pattern to that of a ransomware attack. Despite this link being discovered, their hands were tied for the moment. With the release of the “good and naughty list”, they repeated their threat to release information unless a ransom was paid, and again MediBank quietly refused (UpGuard Team, 2022).

The day after the release of the “good or naughty list”, November 10th, 2022, more information was released, this time regarding MediBank records of customers who received abortions, pregnancies, and miscarriages. From here on, it devolved into a pattern of the hackers releasing information and repeating their demands for $10 million USD to be paid to them until in December they announced, “Case Closed”. Although the leak of data had stopped, trouble still mounted for MediBank in the form of legal battles. They were investigated by the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) in December for their compliance in handling personal and medical information, and sensitive data. Even to this day, they face several ongoing class action lawsuits related to the data breach (Barbaschow, 2023). Now that a sufficient timeline of events has been established, let’s investigate the tools and methods used in the breach.

How did this breach occur, and who caused it?

As we’ve established already, the group who initiated the data breach clearly had ties to the formerly active Russian cyber-criminal group REvil. REvil were known for primarily utilizing ransomware-as-a-service, as well as vetting any potential affiliates or members, only allowing in highly skilled members of primarily Russian speakers and those that live in territories comprising the former Soviet Union (Bukauskas, 2022). Investigators have speculated that the attack was originally meant to be a ransomware attack, but the breach and backdoors were discovered before they could initiate successful encryption.

With all this in mind, we can outline how the attack took place. First, the credentials of a third-party business partner with high-level authorization were stolen and uploaded to the dark web for auction. This information would have given even a novice hacker a way in, but for the REvil affiliated perpetrators, it would have been all too easy to exploit this vulnerability to its full extent, given enough time. As it is, they utilized these access credentials to infiltrate the databases, and establish two backdoors into the system, to avoid detection moving further. To further avoid detection, they created a script that would copy data files on the MediBank database automatically, and eventually one of the hackers compressed this information into a large, 200GB .ZIP file, and extracted it via one of the backdoors.

At this point, and to the credit of the cybersecurity team at MediBank, they were able to detect and shutdown the backdoor and credential access before it escalated to a full-blown ransomware attack by way of database encryption. It’s important to establish that, while the damage done via the data breach was massive, it could have been much more catastrophic for the company had their cybersecurity team not been swift in their response. This emphasizes a need not only to prevent cyber-attacks but respond to them when they eventually occur. You can’t prevent 100% of attacks, but you can prevent how much damage they do in the long-term

Back to the matter at hand, despite the backdoors and all access being cut off, the hackers had what they already wanted. Even though they couldn’t ransom the database, they could still attempt to extort the company and individuals for the stolen information. Despite continued attempts to extort MediBank, publicly they never budged, and all the information was seemingly drip-fed onto the darknet. There were no advanced tools, or methods used by the hackers, just simple backdoors, scripts, and a way in. I think this attack, while simple, emphasizes not only a basic need to limit the credentials to parties outside of an enterprise, as well as highlights the need to have an emergency plan outlined in the unfortunate, yet eventual case of a successful intrusion.

Works Cited:

Barbaschow, A. (2023, February 24). Medibank confirms stolen credentials were used to access its network. Gizmodo Australia. Retrieved April 5, 2023, from https://www.gizmodo.com.au/2023/02/medibank-cyber-incident/

Kost, E. (2023, March 2). What caused the Medibank Data Breach?: Upguard. UpGuard. Retrieved April 4, 2023, from https://www.upguard.com/blog/what-caused-the-medibank-data-breach

MediBank Private Limited. (2022). History. Medibank. Retrieved March 30, 2023, from https://www.medibank.com.au/about/company/overview/history/

Phillips, L. (2023, January 27). Healthcare cyberattacks increasing in 2023. Insider Intelligence. Retrieved March 30, 2023, from https://www.insiderintelligence.com/content/healthcare-cybersecurity-2023-hive-s-shutdown-good-news-cyberattacks-only-getting-worse

Powell, O. (2023, March 24). A full timeline of the Medibank Data leak. Cyber Security Hub. Retrieved April 4, 2023, from https://www.cshub.com/attacks/news/iotw-everything-we-know-about-the-medibank-data-leak

Taylor, J. (2022, October 24). Medibank hack started with theft of company credentials, investigation suggests. The Guardian. Retrieved April 4, 2023, from https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2022/oct/24/medibank-hack-started-with-theft-of-staff-members-credentials-investigation-suggests#:~:text=The%20attack%20is%20believed%20to,not%20authorised%20to%20speak%20publicly

2 Comments Add yours