Progress Report: January 2014

The first IUCN Red List Workshop for Marine Bony Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico was hosted by the Harte Research Institute for Gulf of Mexico Studies in Corpus Christi, Texas, USA from 6-10 January 2014. It was made possible by a generous grant from the U.S. National Fish and Wildlife Foundation.

This workshop focused on mostly shallow, coastal species and ranged from some of the smallest fishes such as the gobies to one of the largest such as the Goliath Grouper (Epinephelus itajara). Six members of the MBU team facilitated 447 assessments with 25 experts. Notably, there were 22 different institutions represented from across Cuba, Mexico, and the United States.

In addition, researchers at the Harte Institute conducted a half-day Marine Observation Protocol workshop where open discussion took place on the development of a species database tool to be designed for the utility of resource managers responding to some disaster event (i.e. oil spill). Given the knowledge of the extent of an event, factors such as a species’ distribution, habitat preferences, and/or Red List category in the Gulf of Mexico may help pinpoint those that would be impacted greatest.

Preliminary results of these assessments show that the majority of the species were assigned to Least Concern (92%), while 20 of them (4.5%) qualified for a Threatened category with four additional species designated as Near Threatened. Furthermore, 3% (12 species) were listed as Data Deficient. Species listed at an elevated risk of extinction were variously impacted either by overexploitation, habitat degradation, or predation by the invasive Lionfish. Considering that the Lionfish invasion has just recently been documented to occur throughout the entire Gulf, we surmise that this threat will receive further region-wide attention from researchers as their populations increase. Another threat highlight lies within the groupers, which tend to be highly valued, large-bodied, long-lived and susceptible to overfishing throughout the region. The implementation of improved fisheries management in U.S. waters has allowed for some localized recoveries, however, lack of management in Mexican and Cuban waters is cause for serious concern. These initial results underscore the importance of characterizing the status of biodiversity found in this ecologically and economically important body of water that experiences an elevated level of risk from natural and anthropogenic disasters.

We look forward to holding a second workshop to assess the remainder of the continental shelf bony fishes as well as continuing to foster collaborative trinational relationships between scientists of Cuba, Mexico, and the United States. We expect that these actions will lead to the establishment and refinement of region-wide marine conservation goals.

Introduction

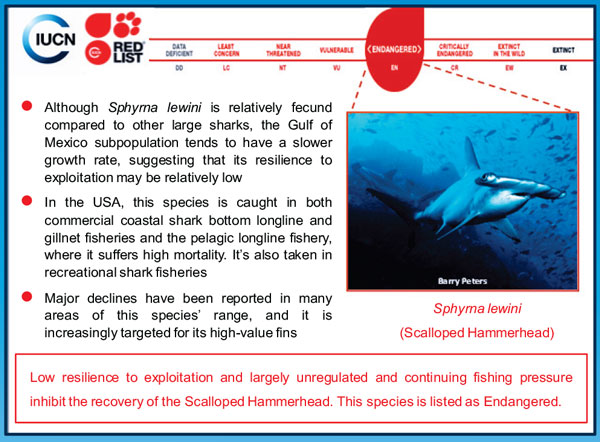

The presence of threatened species on the US Endangered Species Act is often used to define conservation priorities and conduct risk assessments in the Gulf of Mexico. However, currently only 14 Gulf species are afforded federal protection, while at least 53 are currently considered threatened on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (Campagna et al. 2011). Therefore, the identification of conservation priorities in the Gulf is largely conducted in the absence of comprehensive species information. For example, the Scalloped Hammerhead Shark, Sphyrna lewisi, is listed as globally endangered on the Red List (Fig. 1), but it is not protected under the Endangered Species Act (ESA).

Figure 1: Sphyrna lewini is an example of a species in the IUCN Red List listed as Endangered but which lacks ESA protection.

To address this gap, IUCN, in collaboration with Harte Research Institute (HRI), will complete regional-level Red List Assessments for Gulf species (including all marine fishes, mammals, sea turtles, seabirds and selected plants and invertebrates). This comprehensive dataset (including range maps), will help develop a spatial modeling capacity to incorporate into HRI’s existing Biodiversity of the Gulf of Mexico (BioGoMx) database (Moretzsohn et al. 2011), improving knowledge of threatened species and allowing for more effective identification of site and species-specific conservation priorities, risk assessment, disaster preparedness, and recovery of natural resources in the region.

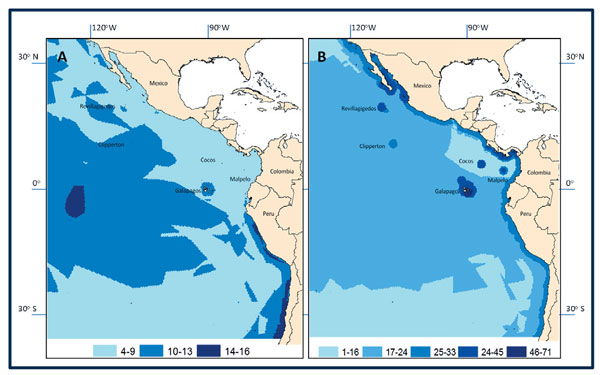

The only other region in the world where comprehensive species-specific Red List assessments have been conducted is in the Eastern Tropical Pacific, where 12% of the more than 1600 species assessed were determined to be in IUCN Red List threatened categories (Polidoro et al., 2012). Previously-available assessment of only marine mammals, seabirds and sea turtles did not provide enough information to easily identify areas of high biodiversity, comprehensive patterns of threat, or nearshore marine conservation priorities (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2: Threatened species richness within the Eastern Tropical Pacific before (A) and after (B) a comprehensive regional assessment initiative (Polidoro et. al. 2012).

However, comprehensive assessment of all known marine vertebrates, as well as selected invertebrates and plants, such as corals, seagrasses, and mangroves, not only provides knowledge of additional threatened species, but also can highlight specific nearshore areas of high species richness of threatened species and patterns of threat. This knowledge, combined with the species-specific information from Red List assessment (e.g., taxonomy, distribution, population status and abundance, habitat, ecology, quantification of major threats, and conservation measures), can transform both site- and species-specific marine conservation priorities for improved risk assessment and disaster preparedness.

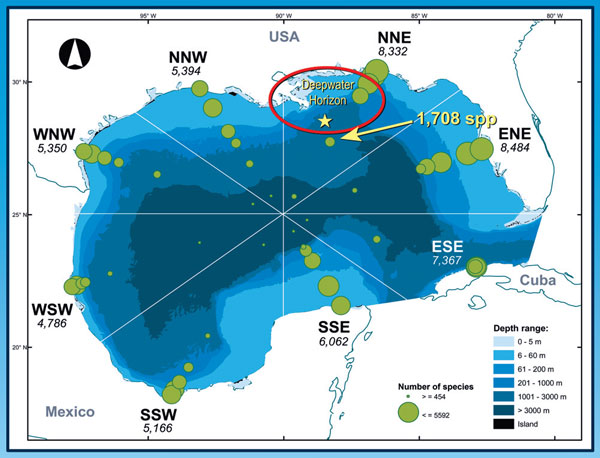

Figure 3: Biodiversity of the Gulf of Mexico based on all 15,419 species included in the BioGoMx online database (based on Felder and Camp, 2009).

The Biodiversity of the Gulf of Mexico database is based on a comprehensive inventory of the marine biota of the Gulf (Felder and Camp, eds., 2009), from a collaboration of 140 experts from 15 countries. BioGoMx has information on 15,419 species from 40 phyla/divisions (Fig. 3), with a page for each species containing updated taxonomy, bathymetric range, habitat, range of distribution in the Gulf, etc. The database is hosted by GulfBase, a portal of GoMx research that includes contributions from over 490 institutions and some 2300 scientists.

Strategy and Conservation Outcomes

Global Red Lists assessments have already been completed for all species of marine mammals (Schipper et al., 2008), sea turtles, seabirds (Croxall et al., 2012), sharks and rays (Dulvy et al., 2008), mangroves (Polidoro et al., 2010), seagrasses (Short et al., 2011), corals (Carpenter et al., 2008), reef-building oysters, lobsters, cephalopods, and sea cucumbers (Purcell et al., in prep.) present in the GoMx. In addition, about 800 of 1541 species of bony fishes in the GoMx have already been assessed globally. Remaining bony fishes will be assessed in regional-level IUCN Red List workshops.

The resulting data, including digital distribution maps, will then be incorporated into HRI’s BioGoMx database. A spatial modeling capacity for disaster preparedness and risk assessment within the GoMx will be developed. A workshop with the goal of establishing a “Marine Observation Protocol,” a standardized agreement on acceptance of occurrence data points into spatial analysis tools will be held; eligible marine point data incorporated into BioGoMx. The availability of a comprehensive, regional marine species database, including designation of each species status under the IUCN Red List, will provide standardized species-specific data for a wide range of conservation and risk assessment activities.

Red List Methodology

The Categories and Criteria of the IUCN Red List have been rigorously developed over the past 40 years and are the global gold standards for assessing a species probability of extinction. For each species to be assessed, the IUCN MBU collects data on taxonomy, distribution, population status and trends, habitat requirements, ecology, threats, and conservation actions. This information is then used to assess each species probability or risk of extinction, expressed as an IUCN Red List Category (Fig. 4), using scientific criteria (IUCN, 2001). To qualify as threatened (listed as Vulnerable, Endangered, or Critically Endangered), the associated quantitative thresholds for at least one of five criteria must be met.

Figure 4: An illustration of the Categories (left) and Criteria (right) of the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (IUCN, 2001).

Deliverables

This collaborative initiative between IUCN and HRI will produce:

- Regional IUCN Red List status of approximately 2,000 GoMx species, including all marine vertebrates (mammals, seabirds, sea turtles, and fishes), and selected invertebrates and plants. This information will be incorporated into BioGoMx and make freely available to the public

- Global IUCN Red List status of ~600 marine bony fishes, which will be published on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species website

- Individual digital range maps for each species created in a GIS (Fig. 5)

- Summary information on taxonomy (assisting identification needs); quantitative information warranting the designation of Red List threatened category (vulnerable, endangered, or critically endangered)

- A spatial modeling capacity and improved mapping capacity for BioGoMx

- A workshop for standardizing acceptance of occurrence data points to establish a “Marine Observation Protocol” for incorporating point data into spatial analysis tools

- Publications in the peer-reviewed literature summarizing the conservation status of GoMx species and highlighting the significance of the process to legal authorities for resource recovery

- Propose the regional assessment and monitoring model to the IUCN Red List Committee for consideration of adoption for other priority regions

- Identify and create a researchable roster of GoMx scientific experts in Gulf Base

- Associated press releases will ensure dissemination of results to a wider popular audience

References

Butchart, S.H.M., Akçakaya, H.R., Chanson, J., Baillie, J.E.M., Collen, B., Turner, W.R., Amin, R., Stuart, S.N., and C. Hilton-Taylor. 2007. Improvements to the IUCN Red List Index. PLoS One 2(1): e140.

Campagna, C., Short F.T., Polidoro, B.A., McManus, R., Collette B. et al. 2011. Gulf of Mexico oil blowout increases risk to globally threatened species. BioScience 61: 393-397.

Carpenter, K.E., Muhammad, A., Aeby, G., Aronson, R.B., Banks, S., et al. 2008. One third of reef building corals face extinction from climate change and local impacts. Science. 321: 560-563.

Croxall, J.P., Butchart, S.H.M., Lascelles, B., Stattersfeild, A.J., Sullivan, B. et al. 2012. Seabird conservation status, threats and priority actions: a global assessment. Bird Conservation International 22:1–34.

Dulvy, N.K., Baum, J.K., Clarke, S., Compagno, L.J.V., Cortes, E. et al.2008. You can swim but you can’t hide: The global status and conservation of oceanic pelagic sharks and rays. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 18: 459-482.

Felder, D.L. and D.K. Camp, eds. 2009. Gulf of Mexico–Origin, Waters, and Biota. Vol. 1. Biodiversity. Texas A&M University Press, College Station, Texas. 1393 pp.

Hoffman, M., Hilton-Taylor, C., Angulo, A., Bohm, M., Brooks, T.M. et al. 2010. The impact of conservation on the status of the world’s vertebrates. Science 330: 1503-1509.

IUCN 2001. The IUCN Res List of Threatened Species. 2001 Categories and Criteria (version 3.1). http://www.iuncredlist.og/static/categories_criteria_3_1.

Moretzsohn, F., J. Brenner, P. Michaud, J.W. Tunnell, and T. Shirley. 2011. Biodiversity of the Gulf of Mexico Database (BioGoMx). Version 1.0. Harte Research Institute for Gulf of Mexico Studies (HRI), Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi, Corpus Christi, Texas. Available online at: http://www.gulfbase.org/biogomx/.

Polidoro, B.A., Brooks, T., Carpenter, K.E., Edgar, G.J., Henderson, S. et al. 2012. Patterns of extinction risk and threat for marine vertebrates and habitat species in the Tropical Eastern Pacific. Marine Ecology Progress Series 448: 93-104.

Polidoro, B.A., Carpenter, K.E., Collins, L., Duke, N.C., Ellison, A.M. et al. 2010. The loss of species: mangrove extinction risk and geographic areas of global concern. PLoSONE 5(4): 1-10.

Schipper, J. et al. (+100 authors). 2008. The Status of the world’s land and marine mammals: Diversity, threat, and knowledge. Science 322: 225-230.

Short, F.T., Polidoro, B., Livingstone, S.R., Carpenter, K.E., Bandeira, S. et al. 2011. Extinction risk assessment of the world’s seagrass species. Biological Conservation 144: 1961-1971.

Recent Comments