Remembering the events of the Holocaust is a complex task, one that extends way beyond Auschwitz-Birkenau. Between 1941 and 1942, around 1.3 million victims were claimed by Nazi mobile killing units and their auxiliary support groups. Even though this number surpasses the victims of Auschwitz, the history of these mass executions has largely been forgotten until recently. Yahad In Unum, an organization established by Father Patrick Desbois, dedicates its work to uncovering the stories of this complicated past. Since its establishment in 2004, the team members of Yahad In Unum have recovered data concerning 2,133 execution sites and recorded over 5,298 testimonies, spanning 8 different countries. Our group had the incredible and unique opportunity to work with a team from Yahad In Unum to see several mass execution sites and speak with two witnesses.

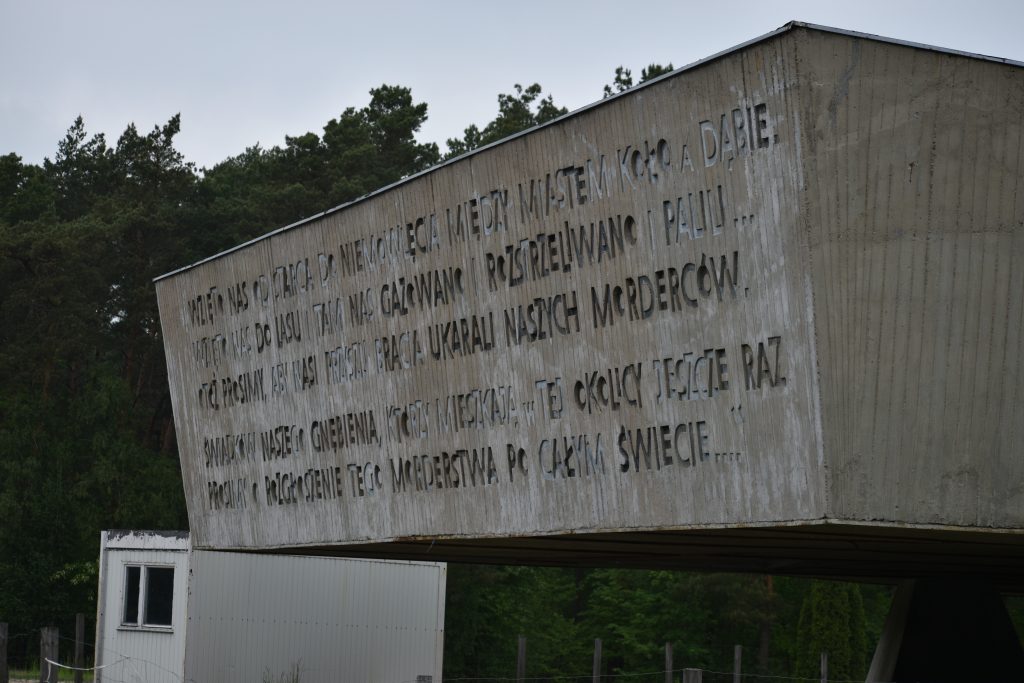

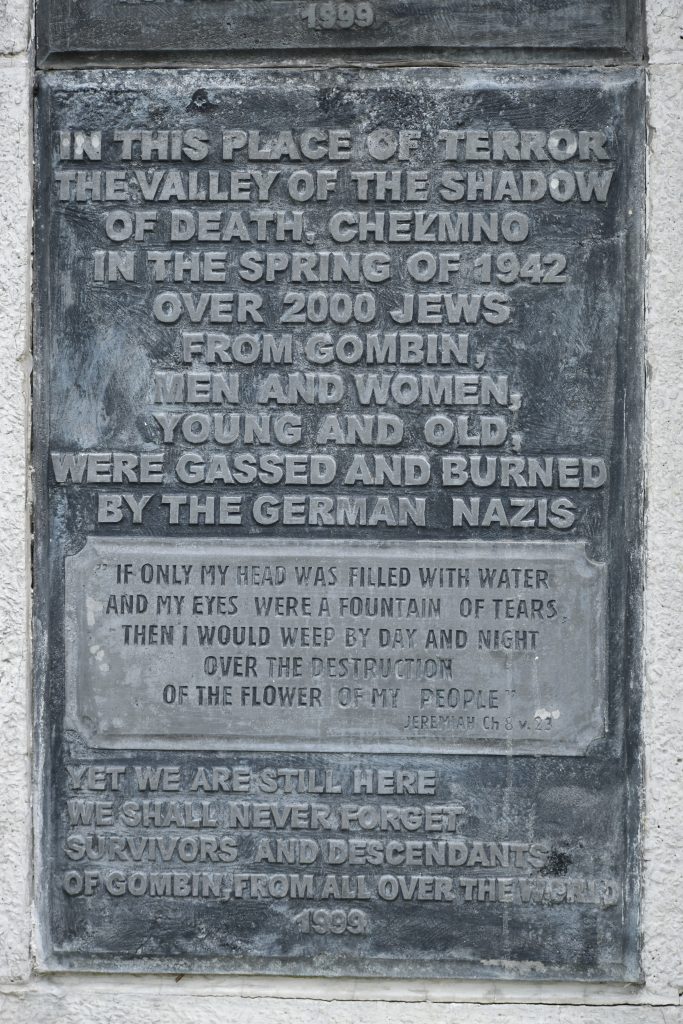

All of the sites we saw, to include two Jewish cemeteries, are desolate and forgotten, but on an entirely different level of isolation from that of sites like Treblinka or Chelmno. Like most Jewish cemeteries of the pre-war era, the two we visited had been destroyed by the Nazis during the war and are now in disarray. Many of the headstones were removed and used to pave the roads during Nazi occupation, and those that were returned afterwards are either inaccurately placed or simply piled up in a corner of the cemetery. There is no Jewish community left in either town we visited, so it is hard for the memory of these sites to be respected or observed.

However, the memory of these sites is not completely forgotten, as there are still some witnesses left to share what life was like before and during the war in these isolated towns. Yahad In Unum works tirelessly to ensure that the stories of these witnesses are documented and added to the history of the Holocaust. We were able to observe their team conduct interviews with two witnesses, getting briefed on how to formulate questions to get factual information and on the importance of keeping your bearing in the face of blunt recollections of tragedy. One of the witnesses, Janvakivsz P., spoke with us about his experience during the war when he was only 12 years old. Even at the age of 89, he was animated and lively, eager to share his story. We were able to hear his story about how he and his mother hid two Jewish men in a cellar under their kitchen. After pealing up the floorboards in his kitchen to reveal that same space, he explained how he had helped provide the hidden men with water and kept a look-out for German patrols at night. Climbing into the cellar myself was one of the most profound experiences I have ever had. Being crunched up in a less than 4 foot tall cellar helped me realize the importance of collecting interviews and story’s like Janvakivsz’, which help add powerful unique and personal stories to the general narrative of the Holocaust.

We then followed Janvakivsz to a Jewish cemetery nearby where he had been witness to an execution. As a young boy, he climbed the back wall of the cemetery to see what was going. He explained to us how the Nazis carried out these actions, detailing how the victims were arranged and shot. Finally, he showed us the train platform where he told us the Jews of his town were taken and then deported to extermination camps in the East (Treblinka). Yahad In Unum’s mission here is so important. We very well may be the last group to get to speak with these witnesses, with their stories being heard for a final time. Each memory shared at these different sites can be corroborated with the known history of the area, and helps piece together blank spots in history.

To add to this already incredible experience, the Yahad In Unum team look us to two mass execution sites in the middle of the forrest. The first one was a barely visible divot in the earth. If you were unaware of the history of that small spot in the woods, there would nothing to indicate that hundreds of people were killed here, where their bodies still remain. The second site was immensely larger. As we passed through the clearing, one of the members of our group softly said, “Oh God.” ‘Oh God’ was right. The pit before me seemed like a clearly visible and painful wound in the earth. Yet, once again, there are no markings, no plaques, no boarders to protect it. Alcohol bottles and plastic littered the site, and a walking path runs straight through it. Over 1.3 million victims of the Holocaust were killed in sites like this one, and the lack of memory present at these wooded sites resembles the lack of memory in the global community. The work of Yahad In Unum to gather and create this collective memory is more important now than ever before. As these witnesses begin to disappear, so will their stories.