By Special Collections and HIST 368 Intern, Daniel Conner

The Story of C.3.3.

Upon beginning my research for National Poetry Month, I stumbled upon a rather interesting author in the Special Collection; someone by the name of C.3.3. I assumed such a tag could be nothing more than a stage name, but after finishing the ballad and conducting some light research, I came across quite the little discovery. C.3.3. was a cell number, and the work that was born from that cell, the Ballad of Reading Gaol (pronounced ‘redding jail’), was explicit, enthralling, and excruciatingly visual.

C.3.3. a.k.a Oscar Wilde was one of, if not the most well known and respected, Irish writers of the late 19th century. However, he was eventually arrested for homosexual conduct and placed in cell C.3.3. of Reading Gaol. Wilde composed plays, novels, and poems that are still considered to be masterpieces today, such as The Importance of Being Earnest, The Picture of Dorian Gray, and Salome. Nevertheless, none of these pieces compare to the dreading reality of Reading Gaol. Within 109 stanzas, Wilde managed to fluidly compact the maddening conditions of a 19th century prison, a description of a murder’s emotions during the act of taking their lover’s life, and the eeriness of near daily capital punishment. Wilde himself experienced the execution of C.T.W., a man who murdered his own wife in a fit of rage before being sentenced to capital punishment. Through the color red, and the feelings of overwhelming love and fear, Wilde managed to portray his understanding of C.T.W. and paint his psyche in a way any reader could comprehend. Furthermore, Wilde wrote on the awful conditions of prison and how any prisoner would certainly become maddened by the end of their sentence if fortunate enough, or perhaps unfortunate enough to live. To list some of the harsh conditions: in the 19th century, anyone from the age of 10 onward could be found in Reading Gaol and the prisoners were forced to wear hoods that covered their eyes when outside of their cells. Meaning, the prisoners were not provided an environment where they could have any true social interaction. The ballad is horrifically real, which is exactly why it’s a terrific read. If you want to read C.3.3.’s short ballad for yourself, ODU’s Perry Library has a later copy on the fourth floor (1971) in addition to the copy in the Special Collections on the third floor (1896).

“He did not wear his scarlet coat,

For blood and wine are red,

And blood and wine were on his hands

When they found him with the dead

The poor dead woman whom he loved,

And murdered in her bed…

The man had killed the thing he loved,

And so he had to die….

Yet each man kills the thing he loves,

By each let this be heard

Some do it with a bitter look,

Some with a flattering word,

The coward does it with a kiss,

The brave man with a sword!”

-C.3.3. The Ballad of Reading Gaol

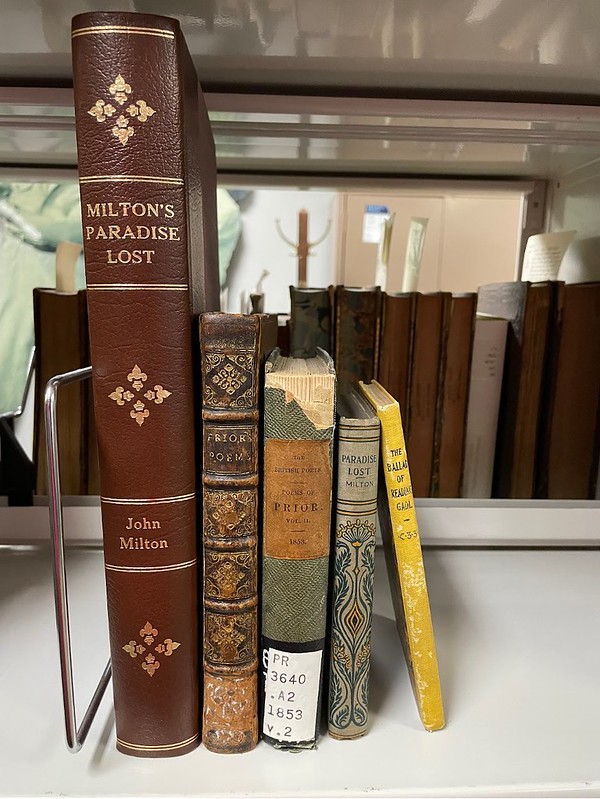

Milton and Paradise Lost

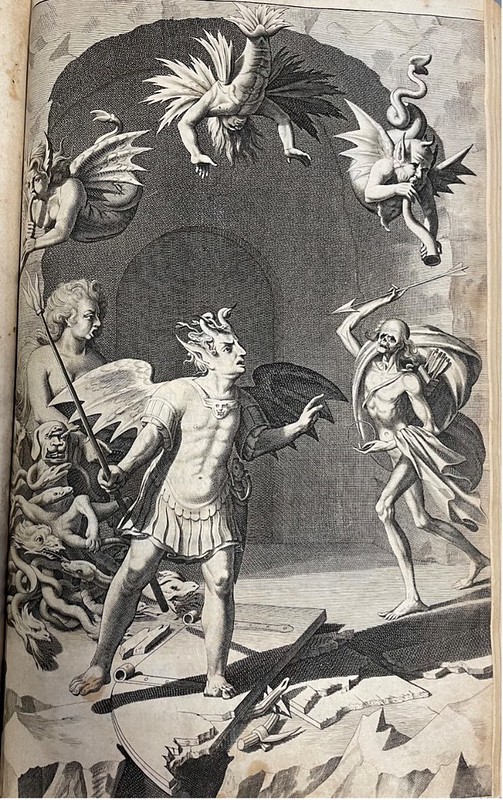

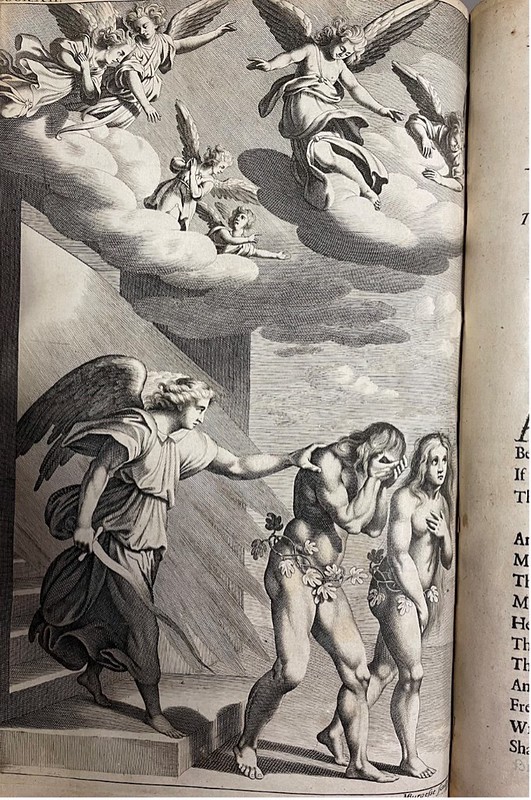

Paradise Lost, John Milton’s iconic poem in 12 books, has sustained its relevance through centuries of controversiality based on a diverse set of historical, political, and religious interpretations. Scholars have analyzed Milton’s intentions and motivations over the past 340 years, but in recent times the appreciation for the religious epic has been in a downward trend. While I could write thousands of words as to why we should value Milton’s work; plenty of volumes of that have already been written and can be found on Perry’s fourth floor. Instead, we can appreciate the beautiful illustrations of SCUA’s 1691 version of Paradise Lost. Two volumes of the epic have been preserved by SCUA, but the 19th century edition, though it features a regal and brightly-colored cover, lacks the imagery of its older counterpart. While not officially credited in this publication, Helen Gardener’s study of the 1688 and 1691 versions of Paradise Lost have attributed the stunning artworks to John Baptist de Medina.The Flemish-Spanish painter’s fluidity, but subtle contrasts between man, demon, and angel perfectly encapsulate the complexity of Milton’s characters. Many readers find themselves sympathizing with Satan and consider him to be the protagonist or hero of the epic. Meanwhile, some may view Satan as pathetic and consider Adam and Eve to be the moral heroes of the story. At the same time, another reader may not consider any of those characters as heroic, and instead rely on the archangel Michael to serve as the loyal, moral being of Paradise Lost. If you’d like to get your hands on Milton’s works and see where you stand within Milton’s battle for heaven, then look no further than the 3rd floor of Perry Library or SCUA’s rare book collection.

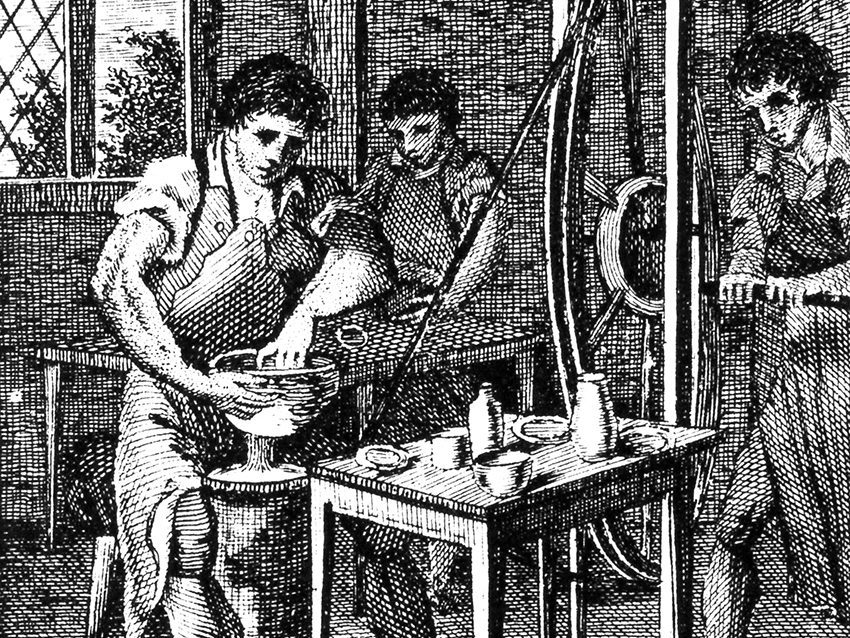

Matthew Prior’s Spellbook of Poems

The gleaming golden engravings on the spine of Matthew Prior’s Poems on Several Occasions immediately drew my attention. Upon feeling the rough leather and studying the beautiful, oversized font, I knew this was a rare book I had to research. Prior, a British diplomat to Louis XIV’s court and the plenipotentiary of Britain’s peace treaty with France during the Spanish War of Succession. Prior had proven proficiencies in foreign language and diplomacy through his experience as a British diplomat to Louis XIV’s court from 1711 until in France. Most notably, he was plenipotentiary of Britain’s peace treaty with France during the Spanish War of Succession, dubbed the Peace of Utrecht. However, what made Prior stand out most from his peers was his special way of composing wit into his writing. Though poetry was more of a hobby than an occupation for Prior, he still excelled as one of the top earning poets of his time.

Before his success abroad, he had 3 volumes of poetry published, two of which were essentially the same. Funnily enough, Prior’s second publication was a pirated version of Poems on Several Occasions. When Prior became aware of the pirated materials though, he expressed his annoyance with the inaccuracies of the volumes, as other authors’ works mistakenly made it into the published volume as well. To adjust the volumes to a standard Prior could appreciate, he re-released his own volume of Poems on Several Occasions two years later in 1709.

After Prior returned from his diplomatic endeavors, he was sentenced to a year in prison based on conspiracies concerning his political party, the Tory party. Due to his imprisonment, his political renown and funds had essentially gone to the wayside. Thus, his friends, including the famous poet Alexander Pope, compiled volumes of Prior’s writings to sell to his fan-base on a consistent basis. The subscribers of his works would be credited at the end of each subscription volume as a show of thanks, similarly to how modern content creators list out their subscribers in the credits of a content piece. Due to Prior’s arrest, his political career was over. Regardless, the ex-diplomat managed to continue to express his views through rhetoric. Thanks to his prowess in sarcasm and massive following, Prior was able to become the first poet to achieve mainstream success through a subscription based publication. If you’re interested in Prior, multiple volumes of his poems are available both on the 4th floor of the Perry Library and in SCUA on the Third Floor.

Sources:

- The Thing He Loves: Murder as Aesthetic Experience in “The Ballad of Reading Gaol” by Karen Alkalay-Gut

- Francis Atterbury and the First Illustrated Edition of “Paradise Lost” by Mary D. Ravenhall

- The party-colour’d life of Matthew Prior (1664-1721)

- St. John’s College University of Cambridge, Matthew Prior (1664-1721)

- The Diplomatic Career of the English Poet Matthew Prior by Liudmila I. Ivonina

- The Shorter Poems of Matthew Prior: Bickley