by Special Collections and HIST 368 Intern Amber Kates

My favorite thing about working in archives is getting lost in the stories. The shelves are a treasure trove filled with others’ memories. Sifting through the pages reawakens moments long since passed. Some interconnect to form entire lives. Others are just snapshots of a single moment, bringing with them an air of mystery. They whisper out questions, begging you to discover their long hidden secrets. But these allurements do not belong solely to the two dimensional world. Artifacts contain their own stories; you just have to know how to read them.

In 2022, the ODU Special Collections was gifted a few pieces of pottery. They were just a small fraction of the 20,000 pieces found during the expansion of I64, headed by the Virginia Department of Transportation. After they were pieced back together by the team at William and Mary, they were placed in the possession of the Coastal Virginia Church – the owners of the property where the pieces were found. The Coastal Virginia Church graciously gave the pieces to the Special Collections. As the intern for the Fall 2022 semester, I was given the opportunity to research a large jug and tankard.

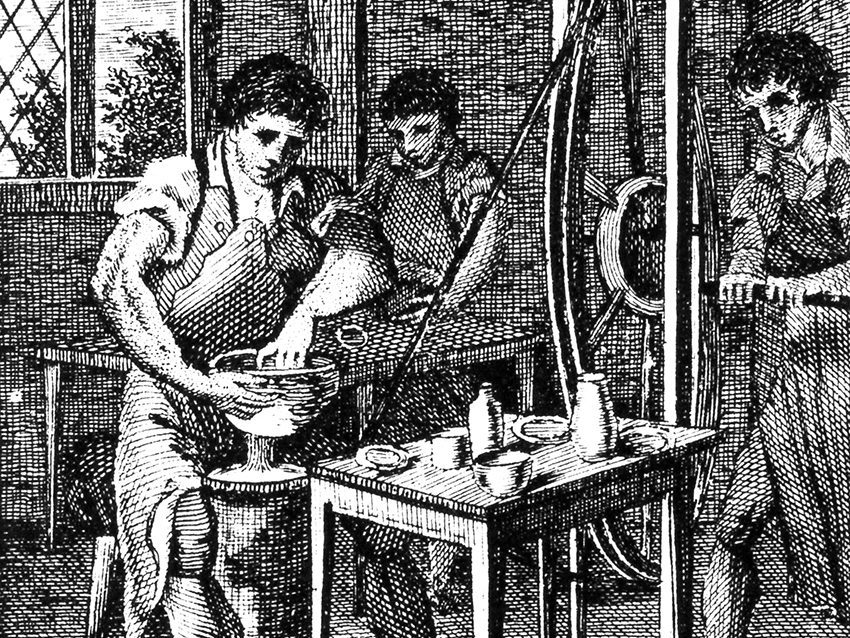

Not much was known about the pottery when it arrived at our Special Collections. They were accompanied by a report prepared by the William and Mary Center for Archaeological Research. Based on this report, it appeared that these pieces were created around the 1730s by the William Rogers Pottery in Yorktown, VA. If everyone was correct, that meant the pieces were almost 300 years old, and a truly extraordinary find!

Assuming that the experts were correct, I dove headfirst into my investigation. When looking at the pieces, they appeared to be common stoneware, consistent of the colonial period. The missing pieces in both the tankard and jug made their fragility obvious. Cracks slither across the jug, indicating places of reconstruction; both handles had been destroyed. The potter utilized a two-tone glaze technique on each piece. Artfully detailed ridges denote the deft hand of the maker. As I studied the jug, my eye was drawn to these drips of green glaze. Not only does the color not match any glaze used on either piece, but the finish is distinct. In contrast to the more matte, gritty-looking finishes, the green glaze is glossy and smooth. These markings are obviously unintentional.

After my initial observations, I began my research. I gathered as many sources as possible on William Rogers and colonial pottery. I read through the report that was sent with the pieces, but it was just a snippet of information. According to the report, the area in which the excavation was conducted was within the site of the old Newtown Colony. Like many colonies in the area, Newtown was an English settlement, and acted as a port for trade. However, by the early nineteenth century, the residents of the area moved on. They discarded whatever wares they couldn’t carry into a giant pit – a pit that wouldn’t be discovered for hundreds of years.

After immigrating from England, William Rogers was a resident of Yorktown colony until the mid-eighteenth century. Often referred to as the “poor potter”, Rogers was anything but. A natural businessman, Rogers had made quite the name for himself with several different ventures. Before building the factory, he was a brewer and merchant. The success from his various enterprises made him a prominent figure in the community, and a wealthy man.

So, why the nickname “poor potter?” Well, it stems from the lieutenant governor of the time, William Gooch. In a 1732 letter to the Board of Trade in London, Gooch mentioned Rogers’ pottery endeavor and stated that it was “of so little consequence.” Then, in 1739 he wrote “The Poor Potter’s operation is unworthy of your Lordship’s notice…” In reality, pottery from Rogers’ factory was transported up and down the east coast and to the West Indies. Gooch’s motivation for the way he handled the situation remains a mystery. After all, what Rogers was doing was illegal. At the time, English law made it clear that goods were to be manufactured in England and then transported to the colonies. Many have stated that Gooch must have been “on the take”. While there was probably some monetary incentive, I believe that the situation was far more complicated. Gooch’s position as lieutenant governor was a balancing act between keeping both Virginia and England happy. He was in charge overseeing the colony and its people while being a soldier for the English Crown. The success of Virginia was good for everyone involved, and Rogers’ pottery was a component of this success. Gooch also knew that he couldn’t turn a blind eye to it. Eventually the truth would be discovered, and there would be consequences.

During this portion of my research, I came across a book that proved to be surprisingly helpful. In, Yorktown, Virginia: A Brief History, author Wilford Kale has an entire chapter on William Rogers and the unearthing of his factory. Included in this chapter was the story of the initial discovery around 1970. According to Kale, the story goes that W.A. Childrey, a Yorktown resident, was sweeping the dirt floor of his garage when he noticed shiny green spots. Curious, Childrey dug a little further and revealed bricks covered in a green glaze. He contacted the College of William and Mary, and the real hunt began (Kale, pp. 30).

My “spidey senses” were tingling. Was this, a brief mention of green glaze, my first clue? Steve Bookman, Head Archivist at the Special Collections, was kind enough to reach out to William and Mary for a copy of the original excavation report. This report described the kiln as being “coated by a thick (1-2 inches) accumulation of a lustrous light to dark green smooth and glass-like glaze” (Barka, 1973, pp. 14). I was like Nancy Drew gathering little fragments of information to solve a mystery.

I knew I needed to go on a field trip and see the site for myself. I reached out to the National Park Service and explained about the pottery and research. I was put into contact with Dr. Dwayne Scheid, Cultural Resources Program Manager and Archaeologist for the National Park Service. He was kind enough to invite me out to the site to discuss this project. I was excited, but nervous. Before I arrived, I emailed pictures of the pottery. Once there, he agreed that they looked like pieces of pottery found during the excavation of the property. However, the only way to really confirm was to get the pieces tested. Dwayne also pointed me to Lindsay Bloch’s work with testing historical ceramics.

I toured the space, which really is the size of someone’s garage. Looking down into the large kiln, it is easy to see the green glaze that was described by Barka. Just as I had hoped, visually it was a match to the drops on the large jug. Dwayne reiterated the need for testing. He explained that the best and easiest thing to do was to first get the pieces tested with an XRF machine. As an undergraduate intern who was clearly in over her head, I just nodded. There was no way that I was going to explain to this very knowledgeable man that I had not even the slightest clue what I was doing, though I’m pretty sure he caught on. I left feeling a little deflated. Was this the end of the road for my project? Nevertheless, I still had a few avenues of investigation to pursue.

Overwhelmed but undeterred, once again, I began my research. Assuming the budget for student-led testing was practically nonexistent, I wanted to find out if the William and Mary’s Center for Archaeological Research had conducted testing during the preservation process. When the pottery was donated to the Special Collections, it was accompanied by a report prepared by William and Mary for VDOT. Reading the report, a second time, I realized that pages were missing. However, several names were listed, including Deborah Davenport. The report stated that she was in charge of “laboratory processing and artifact analysis.” I figured it would be best to go straight to the source and reached out to her with my questions. She informed me that due to their own budgetary constraints they had not performed any testing of the pieces but confirmed their belief that they were created by the William Rogers pottery in Yorktown. She was also kind enough to send me the full report – all 608 pages!

Realizing we were on our own in reference to the chemical analysis, I did a little digging to the basics of XRF testing. This was unknown territory. The Special Collections is not used to diving into the archaeological side of historical preservation. I was able to find a few different institutions who had the ability to help us out but wasn’t sure how many would be willing to assist us pro bono. I once again feared a dead end. On a whim, I contacted the department chair of the ODU Chemistry Department, Dr. Craig Bayse. I explained the situation and asked if we had the testing capabilities. To my surprise, not only did he have access to the equipment, but he was willing to conduct the tests himself.

This is where we are now. The chemical analysis is the final missing piece to confirm if all our work is correct. The wonderful Dr. Bayse conducted XRF testing on both pieces of stoneware. When the results are analyzed, we will be able to determine if the pieces are, in fact, part of the William Rogers collection. I am so lucky to have had the honor to work on this project. It has been an amazing example of different departments and institutions coming together to uncover the truth. Everyone served as an important piece of the puzzle. A special thank you to everyone in the Special Collections. You were all so supportive of me and provided a great learning experience. Jessica Ritchie in particular has been so amazing. She trusted me enough to allow me to run wherever the research led. This has been a truly remarkable hands-on experience.

Director’s Update: After graduating from ODU, Amber has continued to collaborate with the Poor Potter Site and ODU Libraries on a project to trace the pottery back to the site. Amber’s research and ODU’s pioneering chemical analysis methodology could help other repositories and museums officially trace their pieces back to the Poor Potter Site.